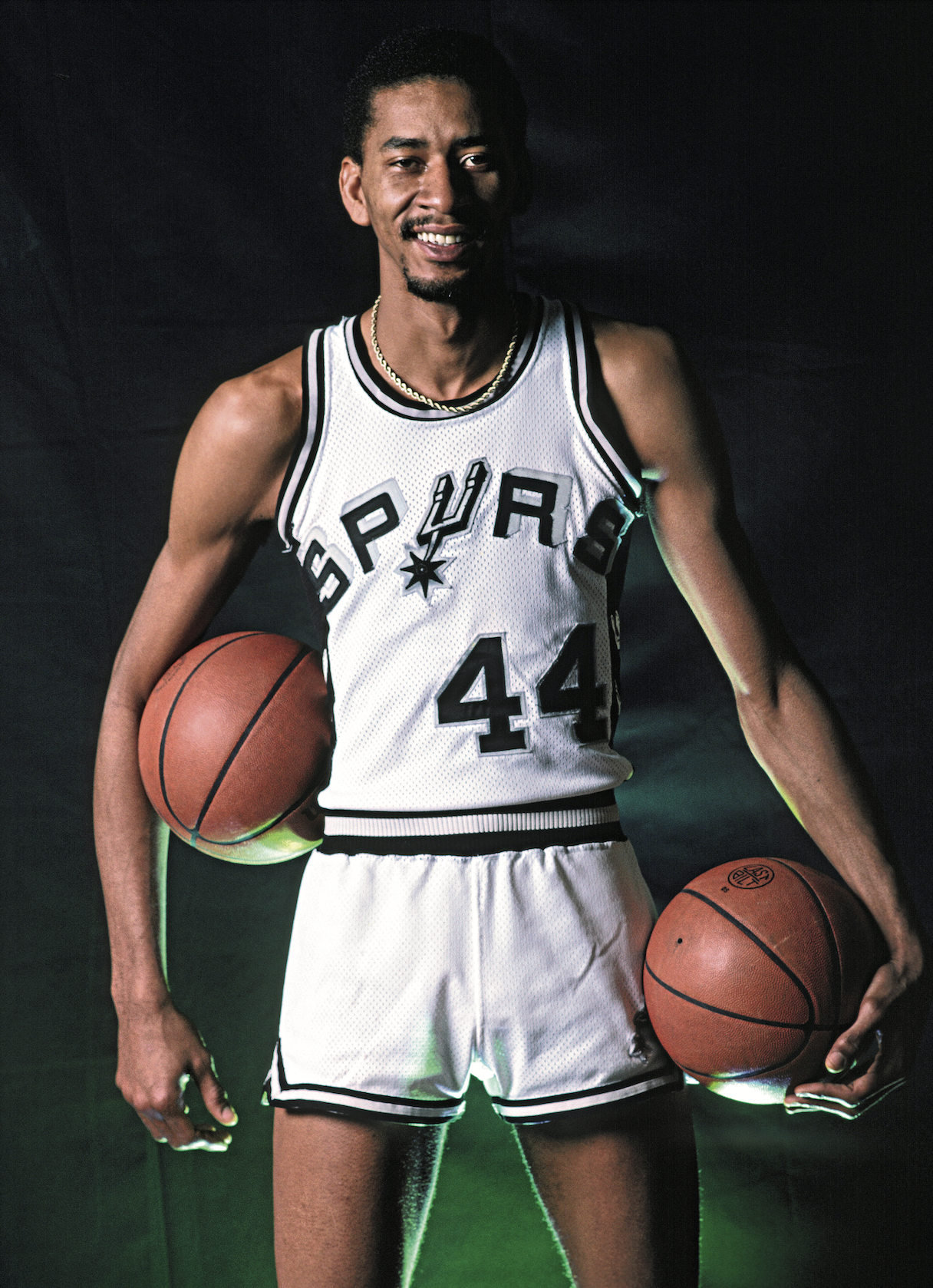

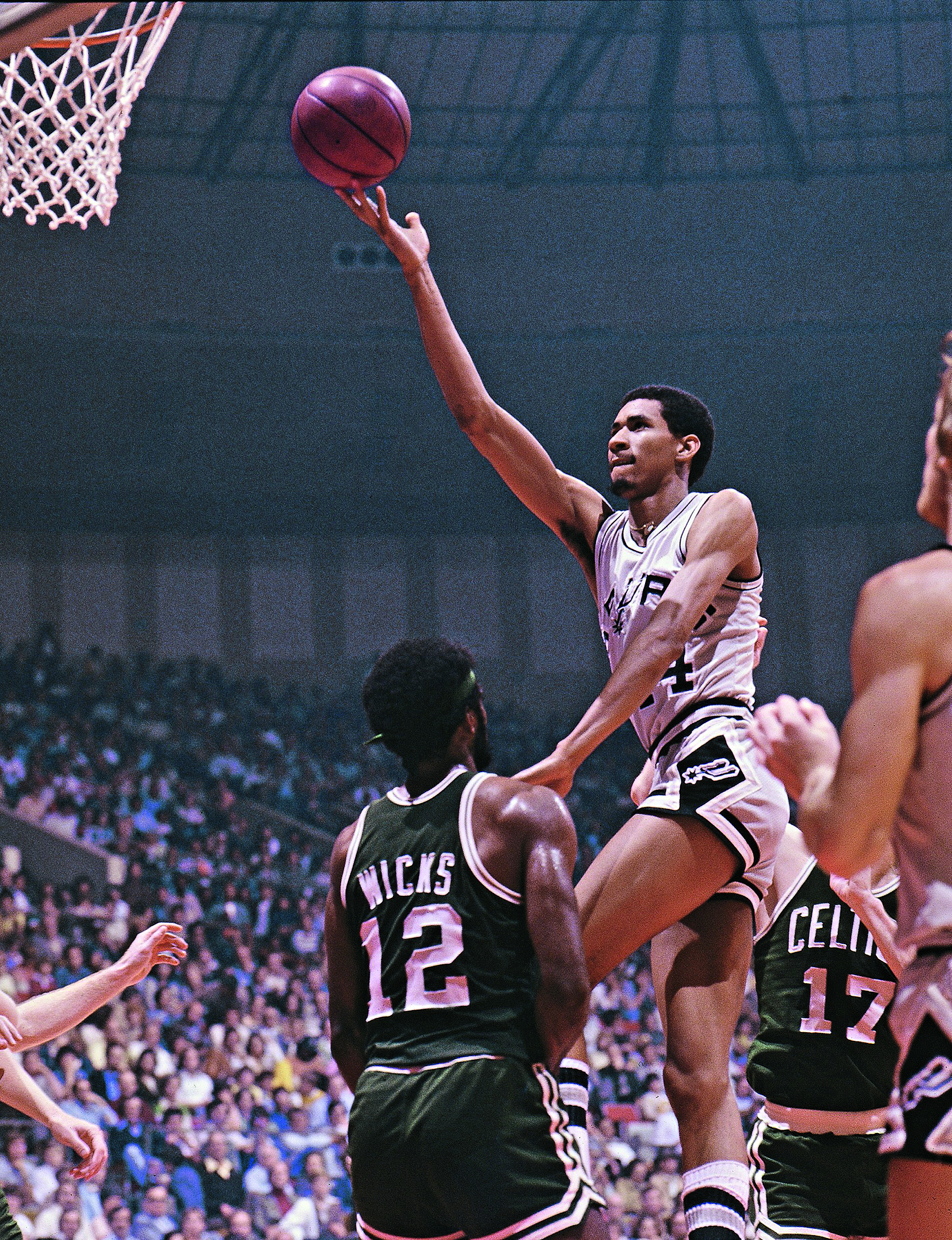

In his new book Ice: Why I Was Born to Score, Hall of Fame legend George Gervin takes readers back to his Virginia Squires days and talks about what he’s up to today.

When I left Eastern Michigan, I went to Pontiac, Michigan, to play for a semi-pro team called the Chaparrals. We played two games on the weekends. I got paid $500 every weekend while playing for a brotha named Roy Washington. And he got me a car so that I could make the games. That car was a Riviera. Emerald green. Beige interior. Big ol’ 8-track. It was nice. And this was in the Continental League, so I was playing against older men. I’m not going to say the Continental League was a bunch of has-beens; it was a bunch of guys who had their turn, and they were like me: coming from bad situations—they got hurt, bad timing, etc.—but they still loved the game, too.

And I was the young buck. They couldn’t catch me back then. I played with them about six or seven months. I was playing well, averaging 30-plus points a game, and Johnny “Red” Kerr saw me. It was after a game against a Flint, Michigan, team led by Justin Thigpen. It was a good game. He and I battled. He was averaging 38 points per game, so he was a bad boy, too. I didn’t know Kerr from the next man on the moon. I don’t remember the conversation I had with Kerr, but somehow Sonny Vaccaro came into the picture, too. I met Vaccaro through Jackson Nunn, one of the football players I went to Eastern with. He introduced me to Vaccaro around 1972 when Vaccaro had the Dapper Dan Roundball Classic. Vaccaro came to meet Coach Merriweather at Merriweather’s house in Detroit. That’s how they hooked up. According to Vaccaro, Nunn reached out to him to help me because of what happened to me at Eastern. Vaccaro apparently had helped Nunn when he was having problems getting noticed and getting a scholarship to college. He was part of the reason Nunn ended up at Eastern. Still to this day, I don’t know why Vaccaro was interested in me. Vaccaro wasn’t an agent. I don’t know where he came from. Somehow, he had a friendship with Al Bianchi, who was then the Virginia Squires coach. From what I was told, Vaccaro made a call, and the next thing I knew, we’re in Virginia.

Vaccaro, Merriweather, and I were in a gym in the Norfolk Scope Arena. Merriweather was talking to Earl Foreman, the owner of the Squires, and Coach Bianchi was up in the stands. And they didn’t know me. They took the word of Kerr who told them they needed to see me. I don’t think Kerr was even in the gym at all that day. He wasn’t even the scout for them. He was their business manager, but I think he had seen me play and knew where I’d fit in—and that was the ABA. I think he just told Foreman to meet me.

And all I remember is they told me to start shooting. It was just me and a few kids on the court who were tossing the balls back to me. I had been warming up already, so when they wanted me to shoot, I started droppin’ ’em. Vaccaro has said that I hit 50 shots in a row, and I was shooting in my street shoes! But I don’t remember that. Knowing me, I ain’t gonna do that. I’m not shooting in my gators. But that’s what Vaccaro says. I don’t know if he’s embellishing it, but I do know that I made a lot of shots whatever I was wearing. Keep in mind I never thought about being a pro. I was pretty content with what I was doing. I was in love with Joyce, I got the game, I got a few bucks, I got a ride, and I’m rollin’. But back then, like Kerr said: I could flat-out score. And I loved that about myself. They said I shot 30 to 35 times, and I made 30 out of 35 or 30 out of 30. But whatever the number was, I heard someone say, “That’s good.” And I stopped shooting right then. After that someone instantly said: “We’ll take him.”

They signed me to a contract. We went into trainer Bob Travaglini’s little office and signed the deal on a paper napkin. At the time they were losing Charlie Scott, who was a special player. I’m glad he got into the Hall of Fame. So again for me this was being in the right place at the right time. Scott was playing for the Squires before I came and I never got a chance to play with him. He went on to the NBA at midseason to the Phoenix Suns. And Scott was big for the Squires. He was like Julius Erving, who was already on the Squires. When I went into their front offices, they had a big picture of Scott on the wall. And I think that’s part of why they were looking at me. Dr. J was right. He said I might be the only person in the history of basketball to literally shoot for his contract, and I did.

This last season, the BIG3 had its first All-Star Game. Dr. J and I were selected as coaches for the All-Star Game. I felt I had the best team, but I was a little disappointed because three of my players didn’t show up for practice for the game. So I told the ones who did show up that they’d be the ones starting in the All-Star Game. Now, from my perspective, the All-Star Game is supposed to be a special thing. At the end of the year, you are one of the 12 guys picked to represent the league, a league you chose to be in. So once I decided to start the ones who showed up, it wasn’t about the game anymore.

If you act like, “Well, I’m gonna show up when I want to,” well, not on me you won’t. And I don’t have to sit up and argue with you or explain myself. My sentiment was: “You might’ve led the BIG3 in scoring, but I led the big league in scoring four times! So, don’t get it twisted.”

I’m the wrong guy to disrespect. But I’m also the same guy who you can learn something from if you want. And this maybe where sometimes the perception of being cool comes into it because of my reaction. I really didn’t care if one or two of the players may have been pissed. To me the game itself is recreation, but the league is something (Ice) Cube put together for the players to stay on stage and make a little money. You gotta respect that. This man done put up all this money to create this opportunity for the players, and that is how they were gonna treat it? I’m not going to yell and scream or disrespect anyone to make them understand that, but in my own way, I’m going to do what I feel is right to make sure a certain level of respect remains.

We live and we learn. And preferably you live long enough to help somebody else out along the way. No matter how hard the lesson. And for coaching that’s when it’s more than basketball for that coach. That’s one of the things I learned from coaching in the ABA in 2000. I coached a team called the Detroit Dogs. I had a bunch of inner-city players. I knew it was very important to tell them in the beginning, “Look here, if I get on you, I’m not getting on you personally. I’m getting on your basketball character.” I wanted them to understand that this isn’t personal. Most of the times, they bought into it, and I didn’t have any issues. I was being upfront with them.

Same thing in the BIG3. I told them, “Look here, this is 3-on-3. We grew up playing 3-on-3. If you forgot that, we not going to win any games. I ain’t coaching, I’m just taking you out when you get tired.” It’s a cool thing Cube is doing. I feel it’s part of my responsibility to make sure those, who are involved with it, respect that. I’m glad he called me to be a part of it. And we really didn’t know each other before this. We only really knew of each other. I remember I’d just got finished working out with Merriweather and got a text: “Hey Ice, it’s Cube. I got something I wanna talk to you about.”

I texted him back, “Who is this?”

He texted, “Cube.”

Then I texted, “Call me.”

He immediately called and said, “Ice, I’m doing this league called the ‘BIG3’ and I want you to be a part of it.”

I said, “Cool, Cube. If you’re going to do it, I’ll do it with you.”

Notice I call him “Cube,” not “Ice Cube.” I told him, “I’m older. I was Ice first.”

This excerpt from Ice: Why I Was Born to Score by George Gervin with Scoop Jackson is reprinted with the permission of Triumph Books. For more information and to order a copy, please visit Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, or TriumphBooks.com/Ice.

Photos via Getty Images.