A black-winged butterfly stops Damian Lillard mid-sentence. He looks up to watch it float through his weight room. It’s doing a solo aerial dance near the highest point in the building, fluttering near the elongated skylight that is flooding the room with natural rays. Several rows of wooden beams support the iron A-frame that’s built above the weights and boxing gear housed here. The wood’s walnut hue and the spectacular blue from the sky give the butterfly a backdrop to show off, striking enough for our interview to come to a pause. Then it’s gone a moment later. WiDamian Lillard th July just about to wrap up, the greater Portland area is experiencing a heat wave. Lillard cut himself off to clock the rarity of seeing a little nature inside his spot, where he’s spent hours and hours under the same skylight. We had left the door open, though, and it flew on through the well-cultivated garden, past the porch’s numerous off-white columns and into his line of sight, catching his eye.

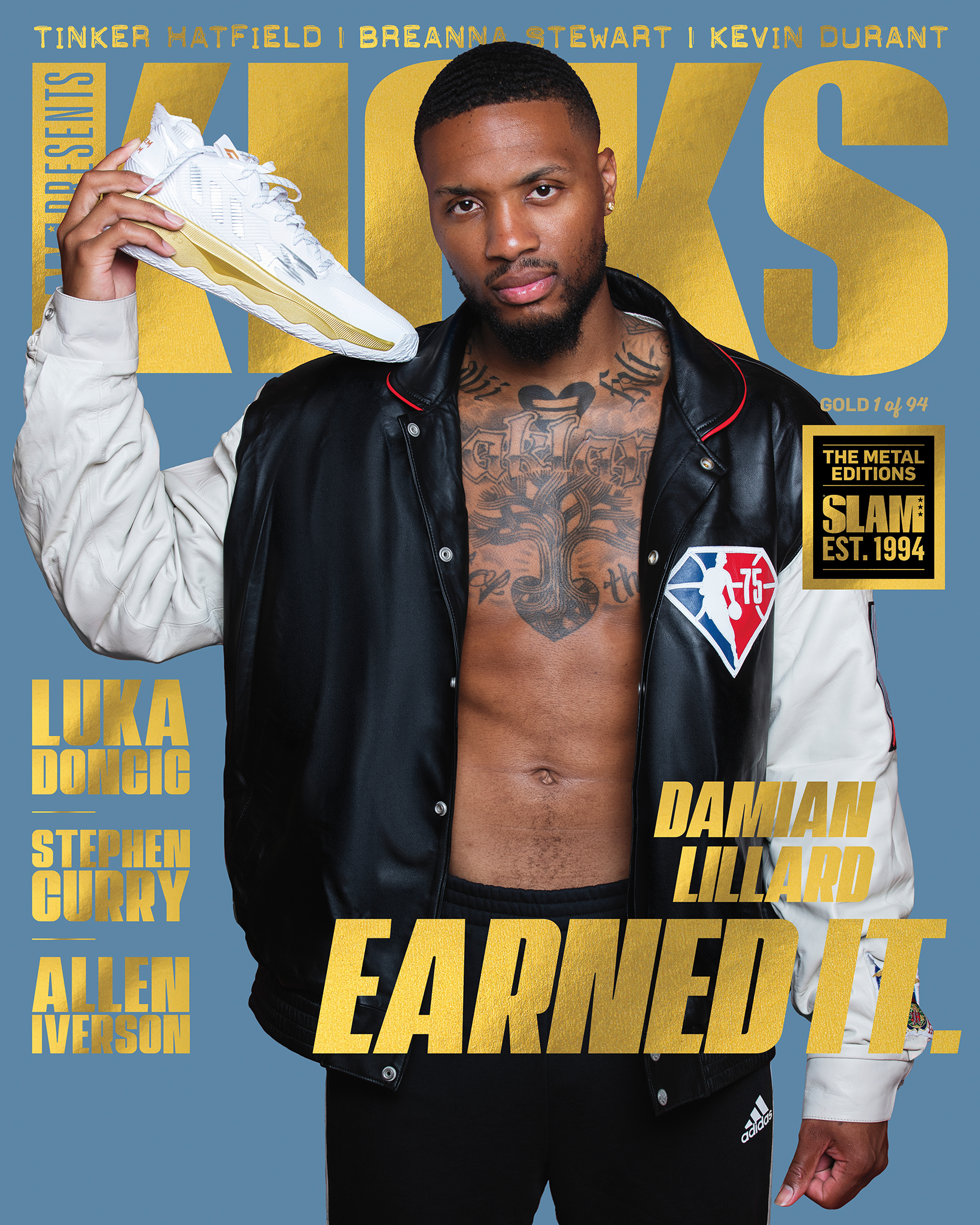

Right after the butterfly finds its way back outside, the conversation with Lillard switches. We’re on to intention leading to instinct, training leading to reacting. Lillard’s a multi-disciplinary expressionist. He uses basketball, sneakers, music and boxing, all to express himself. Every single one of those methods requires practice. Now at 32, with eight adidas signature sneakers, four albums (he confirmed the fifth is on the way) and an NBA career plentiful in the absurd, he’s as experienced as he’s ever been. The work has worked.

KICKS 25 featuring Damian Lillard is out now.

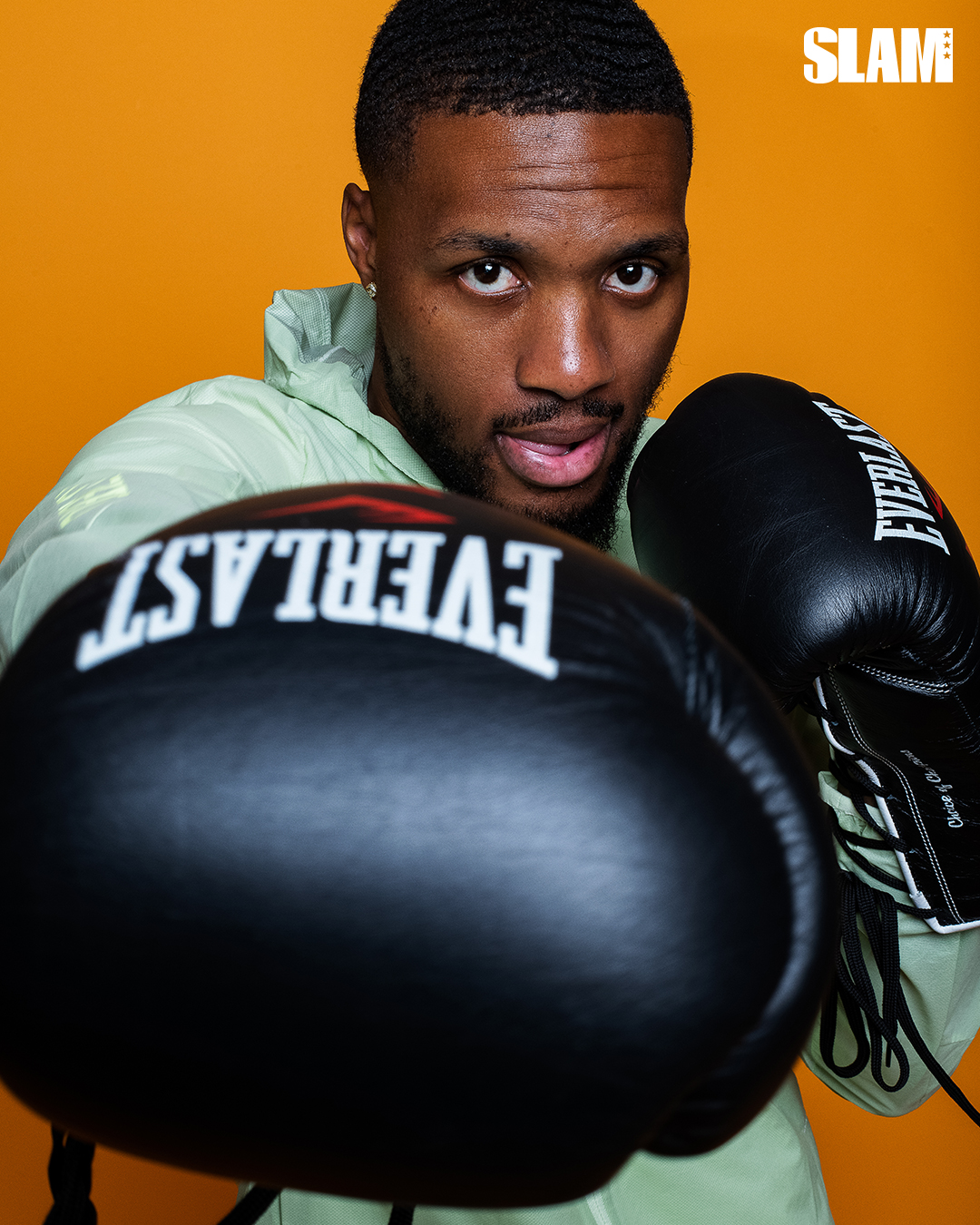

“When I’m in a workout, in a game, that’s when I’m lasered in,” he says. “Like, it’s intentional. Or when I’m in the studio, the beat is looping and it’s just playing over and over and over. And I’m focused on it. When it comes to boxing, sometimes I’ll just be sitting there and I’ll just be shadow boxing to myself. But, like, I’m not thinking about training, you know what I’m saying? It’s still instinctual, you know what I’m saying? The twitch of when I’m training and being able to pay attention and being alert, it’s instinctual. Like, somebody over there just moved and I can see it out of my peripheral.”

He motions to his left side, where a group of his people are watching us. They’re sitting by the same strength training equipment that has helped, in part, to develop the very ability he’s currently talking about. They too have caught his eye.

“That’s boxing,” he goes on. “That’s the instinct to me. So it’s stuff like that. Or when I just come home from training and I’m in the shower and I’m playing my music off my phone, but as the beat is happening, I just randomly start thinking of my own stuff to whatever I’m hearing, you know? I’m not consciously saying shut it off, but when I’m not on, it’s still instinctually happening.”

It all exists at the same time. The thoughtfully-penned lyrics come from the same mind that now knows how to throw a knockout punch. The multicolor variations of his signature sneakers are worn at the same time as when he only sees red on the court. And each version of himself says things that the other versions can’t necessarily get across. He says that words really don’t convey the emotions he feels on a basketball court when he’s in the middle of proving again and again that he’s a Hall of Famer. But, he then says, his face conveys those emotions, as does his body language. The feelings that come with the snap of a sharp punch can’t be described with words either, but he says that hearing contact made from the perfect hit does justice to how incredible and empowering it is.

As an audio artist, he’s become acutely aware of the world’s acoustics.

He brings up his two legendary buzzer-beating, series-ending three-pointers, the first against the Houston Rockets and the second against the Oklahoma City Thunder as examples of the emotion-conveying sounds he’s talking about.

“As the game goes on, sometimes people cheer. You’ll hear the crowd roar a little bit. But when you hit a game-winner, it’s just different,” he says. “It’s like something coming down on you. So I would say that was, like, a perfect moment when you hear it. So against the Rockets and against OKC, I had hit other big shots, but that was, like, the perfect moment.”

And what does he mean by coming down?

“Typically on the court, you hit a buzzer beater in the second quarter, everybody cheers, or you get an and-1,” he says. “But those two specific shots, it felt like the crowd was on top of us. It wasn’t like an everybody’s-in-their-seat type of feeling. It felt like everybody was all up in my space. That’s what it seemed like, because everybody’s standing up and everybody’s jumping up and down and yelling. So it looked different because usually in the game, half the crowd stands up and some people are walking around and a lot of people just sit, you know, throughout the entire game. But in those moments, it’s like everybodys standing up, everybody screaming to the top of their lungs and you can feel it.”

Lillard was wearing the Crazyquick 2 for the Rockets shot and the Dame 5 for the Thunder shot. This season, when he returns after playing only 29 games during the 2021-22 season to recover from abdominal surgery, he’ll be wearing the Dame 8. He’ll have it on his feet while he reminds the far too many people who seem to have forgotten that he’s rightfully earned his way to the NBA’s Top 75 anniversary team, to the $122 million extension he just signed to bring his deal with the Blazers to $225 million overall, to all of his signature sneakers.

The 8 is here in Dame’s weight room. He plays around with the two colorways we have a few times in between the photo setups that are now blocking his row of dumbbells. The 8 is home to a dual-density cushioning system made out of a Bounce Pro (the Dame line has long used Bounce) midsole. The foam used in Bounce is made out of elastic-like EVA (ethel vinyl acetate), providing lots of support and a high return in energy with each step. In this dual-density version, there’s a firm version of Bounce on top of a soft version of Bounce. The Stripes are on the road to sustainability, so the 8 is one of their many silhouettes being made with recycled materials. Those materials include textiles and synthetic overlays on the upper and mesh on the tongue. The medial quarter is carved out for space to let the namesake express himself. The variation he’s holding on the cover of this magazine has a fluffy pull tab inspired by boxing.

The real star of the 8, though, is the outsole. A unique traction pattern gives a peek at the Bounce Pro in action. From colorway to colorway, too, the traction has gotten the chance to look extra spicy.

“The 8 is a shoe that I feel, like, I can wear it straight out the box,” Lillard says. “You know, I’ve had some foot issues over my career, so some shoes feel a little more stiff. And sometimes it’s like, Man, I can’t wear this tonight, I got to break them in. But this is the first one where, like, every time I put these on, even when I wear a brand-new pair, it’s like I can play in them right away. So the comfort is there, the padding and cushion inside the shoe. The grip is really good. I’ve never lost traction with this shoe. Usually, shoes, as you wear them and wear them, you lose traction. This one hasn’t done that. So the way the shoe looks means something to me because it’s one of the best performing shoes that I’ve had, if not the best, and it looks good. A lot of basketball players like to wear shoes that look good or, you know, they flashy colors or loud or whatever, you’re seeing it more and more. And I’m having a lot more colorways like that. But it’s a shoe that’s not just a look-good type of shoe, but then it’s a terrible performance shoe. This shoe is hitting on all cylinders.”

Speaking of those colorways, Lillard cracks the door just a little bit on an upcoming story to be told by a colorway of the 8.

“I just literally came up with this idea,” he begins. “It’s called ‘Damn Gina.’ And it’s a ’90s pack, like, a ’90s theme. I had a bunch of ’90s-themed ideas and it’s called ‘Damn Gina’ because I was a huge fan of the show Martin. I was born in the ’90s and I’ve always done a shoe that was, like, a nod to my mom. My mom’s name is Gina, and it’s kind of, like, how I was saying people are wearing more and more just wild colors? You know, just a mix of different colors. And the Martintheme, when you think of Martin, you think of that old school ’90s, you know, triangles and squiggles, all these different shapes and patterns, but with all these different colors, too. So it’s a shoe theme like that. I thought that was pretty cool, with a bunch of other ones, too. But there’s one that I will mention.”

More expression from Dame.

He’s also learned to, as he said, listen to how his body expresses itself through injuries. After fighting through it for what was probably too long, he had that aforementioned surgery in January. The foot issues he mentions have led him to co-founding Move, a company that makes scientifically-researched insoles for athletics. They have the Game Day Pro model, which Dame uses for his matchups in the League, and they have the Game Day model, which can be substituted into any pair that gets worn while walking around.

“The fact that these kids are constantly training, constantly playing on different teams and travel and doing all these different things, the game is much harder on their feet than it was on ours,” Lillard says. “So that should just tell you how important something like [Move] is for these kids, because the lack of knowledge or even the thought of my foot health led to a foot injury for me. I broke my foot when I got to college because I got flat feet and I never had support in my shoes. I wore flip-flops all the time. And then a couple of years into the League, I had tears in my plantar fasciitis under my feet because I needed some type of support in my shoe and I never had it.”

He’s helped the company to develop the research they started about a decade ago. Their Pulsion Energyfoam combines with the X-Frame torsional support and Active Heel tech to offer as much protection as possible.

Lillard wore the Game Day Pro in last summer’s Olympics, when he and the squad brought back the Gold from Tokyo. He again stresses the importance of foot health, saying “that’s what we live on as athletes, is our feet.”

For as much as he takes care of his feet, through both Move and his signature adi line, he also takes care of his mind, which he’s referred to as a “lethal weapon” in his song “GOAT Spirit.”

It’s easy for us as the public to see all the reps he’s put into his body, into his shot. He’s a marvel in conditioning, able to consistently hit from 35-plus feet out. That takes a ridiculous amount of time in the gym, time that we can physically comprehend through minutes planked and jumpers swished.

Calmly, seated in a chair that came from the back room of his weightlifting gym on our red seamless backdrop, his mind starts to unfurl. It doesn’t take much. As deep a thinker as he is, as willing an expresser as he is, it’s all right there.

“It would be a long timeline, because the way I train now, I didn’t train this way in high school,” he says about being able to visualize his mental journey. “I needed somebody to push me. I got pushed in high school by Raymond Young, but when I got to college, Phil [Beckner] pushed me a little bit more. And he still pushes me now. When I got to the NBA, David Vanterpool pushed me a little bit more. And my dad had been pushing me all the time, just in mental ways. When something would happen in the neighborhood, he’d be like, Man, ain’t nobody worried about them. It was almost like there should never be fear. Why? Why would you be scared? What are they going to do? You know, it was always that type of mentality in my life. So it’s not now, where I’m like a lethal weapon. My whole life has been just developing and people pushing me to develop that way to where, like, in my head, I feel like I got full control mentally, regardless of what the environment is or if it’s going good or it’s going bad. And I also know that a lot of people don’t have that. So that makes it more lethal to me. It’s like I can see that it’s not there.”

Fear isn’t gone. It’s just a different type of fear.

“No, I have fear,” he says. “But my fear is more, like, I’ve got three kids now. So I fear stuff for my kids or my parents getting older or my grandparents getting older and, you know, my cousins being in Oakland, you know, being around stuff. I fear that kind of stuff. But I don’t fear not winning the championship. I don’t fear missing shots or people talking about me on Twitter or a confrontation breaking out. I don’t fear that kind of stuff.”

Because he’s constantly paying attention to his surroundings (a black-winged butterfly, for example), he can see when other people don’t have that type of mental fortitude. He notices body language and picks up on slight cues. He’s barely shifted in his chair throughout this entire answer. Completely relaxed, resolute in all his words, not breaking eye contact. It’s for real. It’s all really for real.

He’s been in enough situations where he chose fight instead of flight to notice when somebody makes the other choice. He decided long ago that he’d remain militant in those moments because confronting was more comfortable than retreating.

“I could fail three times or four times, and I’m just going to keep walking toward it, where you have people that will try to try their best to not be in that situation again, because it’s hard,” Lillard says. “It’s a hard situation to be in. But in my head I’m just, like, I’ve made my mind up that I’m willing to deal with whatever the outcome is and whatever it comes with, good or bad. They don’t have that, you know? They can’t do it. And to me, that’s what I mean by I can see that people don’t have that mentality. And that makes me feel even more dangerous mentally. I feel even more sure about the way I see it.”

Lillard has been showing the nation that he’s a person capable of seeing the unseen ever since he made it to Rip City back in 2012. But there’s a problem; people don’t understand what they can’t see. So he’s still not properly appreciated.

In these pages, that skylight in his gym is a spotlight to properly regard him as an all-time top-five three-point shooter, as one of a small handful to have eight signature sneakers, as an expanded mind, as one of the 75 best players in NBA history, as a multi-disciplinary expressionist, as a man who will stop to watch a butterfly.

“I think through all of those things. I would want people to know who I truly am,” he says about expressing himself. “You know, not just a rapper that’s just saying random stuff. I’m telling my real story and my real thoughts and feelings. As an athlete, I’m really doing what I love, I’m not trying to be another player. I’m not trying to join any other team. I’m just being me. So everything that I’m doing, I’m just trying to get people to see the different layers of me, but not a different me. Just the same, the same person, all around.”

KICKS 25 is available now in this exclusive gold metal edition. Shop now.

Portraits by Alex Woodhouse.