Jaylen Brown. The $300 million man.

Fresh off unequivocally the best season of his career, the Boston Celtics star landed the then-largest contract in NBA history. His All-NBA Second Team selection made him eligible for the supermax, and the Celtics obliged, handing him a five-year, $304 extension.

Unfortunately, between his dominant regular-season campaign and the signing of his shiny new deal, Brown churned in one of the worst performances of his career.

In Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals, Jayson Tatum went down with an ankle injury on the first play of the game, leaving Brown to lead the Celtics, who were on the brink of making history by erasing an 0-3 series deficit. What followed was a testament to the most significant hole in his game.

Brown finished the game with 19 points, eight rebounds, and five assists while shooting 8-of-23 from the field and 1-of-9 from distance. Worst of all, he turned the ball over a career-high eight times en route to a 19-point Miami Heat blowout.

The ensuing vitriol thrown Brown’s way continued into the summer, most of which involved criticism surrounding his handle. Most of Brown’s turnovers game while he was going left, and the idea that Brown “doesn’t have a left hand” quickly spiraled into a meme greater than the problem itself.

But while Brown’s ball-handling certainly leaves something to be desired, it’s merely a part of the larger problem within his game – playmaking.

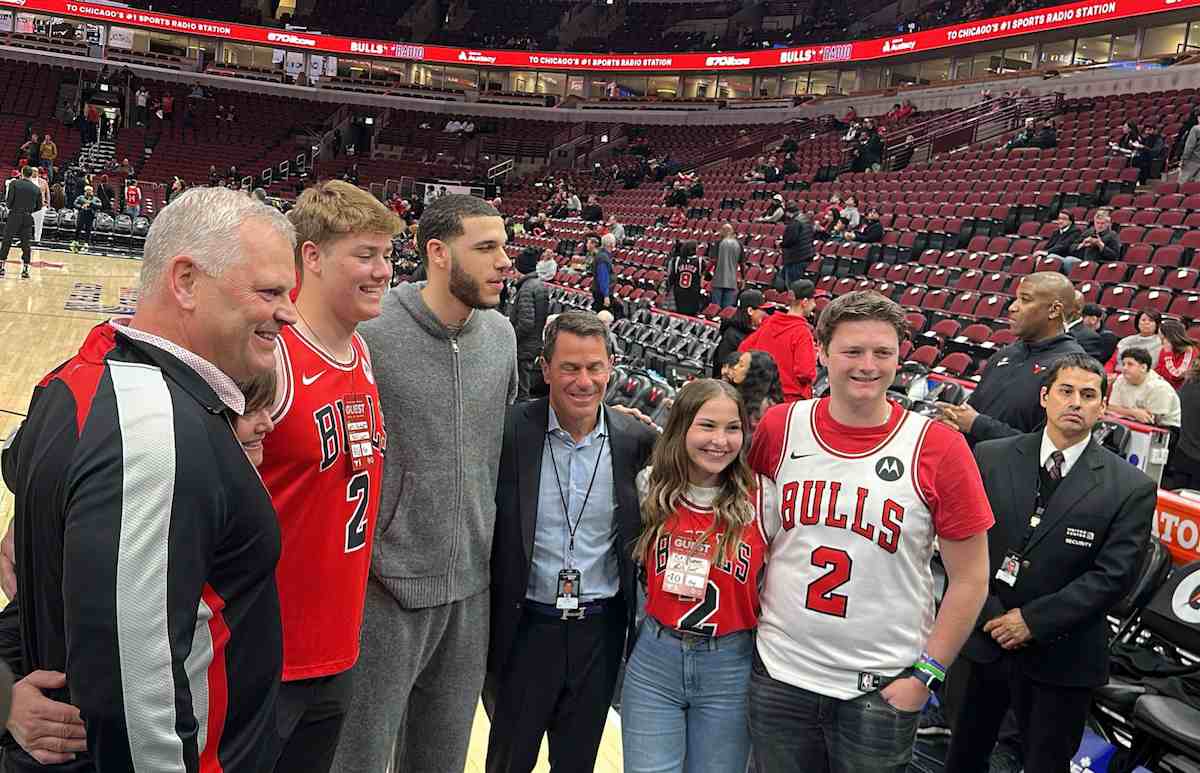

Photo by Stephen Nadler/PxImages/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

The term playmaking has been overused in the context of basketball. Does it mean passing? Does it mean floor vision? Does it mean a quick handle? It’s an all-encompassing word that gets thrown around a bit too much. But in the case of Brown, it’s the perfect term for the area in which he needs to improve the most.

Over the past three years, Brown’s usage rate has increased each season from 29.7% in 2020-21 to 30.5% in 2021-22 to 31.4% this past year. In tandem, his scoring numbers have improved year after year as well. What’s concerning is that his assist numbers have remained stagnant.

Raw assist numbers aren’t enough to quantify the type of playmaker Brown is, but the rest of his passing stats don’t paint an ideal picture, either. Despite ranking second on the team in minutes and passes received, Brown was fifth in passes made and fifth in potential assists.

Brown is too good of a scorer and space-creator to not be setting up his teammates at a high rate. If the Celtics are going to put the ball in his hands as much as they do (and should), he needs to improve.

Last season, Brown averaged 4.3 pick-n-roll possessions per game as the ball handler, which ranked third on the Celtics behind Tatum and Malcolm Brogdon. For context, Tatum ran 5.6 pick-n-rolls per game.

This possession early into last season is a bit awkward. Derrick White doesn’t set a full screen, instead slipping to the basket. Meanwhile, Al Horford has a bit of separation at the top of the key, but Brown tries to force the ball to White. Unfortunately, DeMar DeRozan reads it and nabs a steal.

The real issue on this play is Brown’s decision to leave his feet before making a read. If he had reacted quicker, he could have gotten the ball to Horford, and if he had taken an extra beat, a cross-court pass to Marcus Smart in the corner could have even been a possibility. Instead, Brown leaves his feet, leaving him with no choice but to dump the ball off.

Brown’s first step in the pick-n-roll can also be a problem. When Sam Hauser runs to set a screen, Brown’s first step is inside the three-point line. Michael Porter Jr. jumps him, forces him back into the screen, and Brown turns the ball over. He was so eager to get to his spot on the interior that the Denver Nuggets were able to predict the play before it happened.

Had Brown continued to bring the ball out toward the wing, opportunities could have opened up. White would have kept leaking to the opposite wing, leaving Brown with two options – attacking Porter Jr. on the drive or, if Christian Braun or Jeff Green tried to help, kicking the ball to Hauser or Grant Williams for a three. However, the small decision to step in rather than to the side prevented the play from developing.

Brown’s driving and mid-range game often go hand-in-hand with his pick-n-roll choices. Here, Horford sets a brush screen, allowing Brown to work on the wing. As soon as Brown drives, Nikola Vucevic sinks in, leaving Horford open at the top of the key. If you pause the video when Brown spins, he has a perfect opportunity to kick the ball out to Horford but instead continues his move, leading to a turnover.

This isn’t to say Brown should stop attacking the hoop. He should do it more. Among guards who took at least 300 shots within five feet of the basket, he had the third-best shooting percentage at 68.2%. He’s lethal around the rim.

However, if Brown can convert some of the inevitable double teams he’ll see in the paint into open shots for his teammates, the Celtics offense will benefit. That’s precisely what should have happened on this play.

Sometimes, the adaptation Brown needs to make is as simple as keeping his head up and his options open. The Celtics have the Heat beat on this play. Brown blew by Kyle Lowry, who sold out for the steal, resulting in a one-on-two with Caleb Martin guarding both Brown and Smart.

Once Brown felt himself get past Lowry, one of two choices could have saved the possession – slowing down or making a quicker read. Had Brown taken a beat and slowed down his drive, Martin would have had to commit to either him or Smart, which would have left the other open, or he would have gotten stuck in the middle. Both scenarios would have led to an open shot.

As soon as Brown chose to speed up however, his head should have been on a swivel. His decision to drive quickly caused Martin to step up, which left Smart open under the rim. But Brown’s gaze never left the basket. Once he got by Lowry, he only had eyes for the rim.

Speaking of keeping his head on a swivel, sometimes Brown just needs to make quicker choices with the ball in his hands. It’s not always the case, but the ball sticking to a player’s hands can often be the downfall of a possession.

Brown gets the ball in transition here, and the Celtics have a four-on-four break, but the Heat drop back in coverage. Had he looked around sooner, he could have zipped the ball to Horford on the wing.

Jimmy Butler does an excellent job of cutting off the passing lane, but Brown unfortunately followed up a missed opportunity with another mistake – picking the ball up. As soon as he tried to get the ball to Horford late and picked up his dribble, the Heat transitioned into deny mode. Every lane was clogged, and Brown was stuck.

Brown’s mid-range game is a perfect weapon for Boston’s offense. This was a good shot. There was no need for Brown to pass out of it. However, it’s the perfect example of how much space he creates with his sheer presence in the area.

As soon as Brown beats RJ Barrett off the dribble, the rest of the New York Knicks lineup naturally turns towards him. Jalen Brunson leaves Malcolm Brogdon in the corner, Julius Randle leaves Tatum at the top of the key, and Isaiah Hartenstein starts leaking off of Smart in the corner.

The Knicks were so worried about Brown driving to the hoop that he not only created a mid-range look for himself, but his threat also opened up shots for three of his teammates.

Brown could have kicked this to Tatum or Brogdon for a three, but by the time that pass would have gotten there, Cam Reddish or Brunson would have been able to close out. Rather than eliminating the mid-range from his game, Brown should use it as a tool.

Again, watch the entire defense shift in tandem with Brown trying to get inside. The instant Brown begins his drive against Paolo Banchero, everyone else on the Orlando Magic takes notice. Kevon Harris helps off Smart, and Mo Wagner steps up, forcing Bol Bol to switch onto Horford.

Brown chose to pull up in the paint, an area where he was money throughout the year, but he had options. Had he kept his head up, he could have dished the ball to White or Smart for a wide-open three. Instead of finishing his move and going directly into his shot, all it would have taken was a moment of hesitation for him to find an open teammate.

Again, the shot Brown got on this possession wasn’t a bad one. He created enough space to the point where Banchero and Wagner couldn’t even get a contest off, but he also forced the defense to collapse.

These minute details will help Brown unlock new opportunities within his game and the Celtics offense. And he’s fully capable of making the alterations.

Brown can use his shot creation to set up his teammates. He can make cross-court passes. He can make simple reads. Now, it’s about doing those things more consistently. If he can do that, not only will the Celtics offense get more unpredictable, but he’ll have more space to get his own shots up, as defenses will have to worry about his passing and scoring rather than solely the latter.

With Smart out of the picture, White is set to assume the starting point guard role, but Tatum and Brown will undoubtedly have the ball in their hands more. Smart was the Celtics’ lead creator for the past two seasons, but that duty will be passed on to the stars.

Brown is already an elite scorer. He consistently draws the full attention of opposing defenses with that skill alone. The next step is converting that ability into playmaking. And if he does that, his offensive game will be truly unstoppable.

Just one season after putting up the best scoring numbers of his career, Brown will be tasked with recasting that success into a new area of need. And if he can successfully make the jump from primary shot-taker to a partial offensive hub, his $300 million price tag will go from a necessary investment to an absolute bargain.