Ime Udoka couldn’t have went to the locker room. If he did, it wasn’t for long. Within minutes of R.J. Barrett burying a heave from the right wing and sending the Celtics back to Boston following a 25-point collapse loss with a 18-21 record, all appeared broken when Udoka arrived at the podium.

“Repetitive result, this happening,” he said. “Either we’re going to make some adjustments and get tired of it or it’s going to keep happening … we need some leadership, somebody that can calm us down and not get rattled when everything starts to go a little south, and I think it snowballs between our guys — or do I have to stop all our momentum and pace and call a play? … (It’s) some kind of lack of mental toughness there, where something goes a little bad and we all start to drop our head, or everybody adds to it instead of stepping up and calming us.”

Robert Williams III remembers Udoka privately reassuring him around that time that they’d get it together. The team had lost its defensive poise on a west coast trip and found just about every way to lose a game, from shooting 9.5% from three against the Clippers to stumbling against a Minnesota lineup filled with G-League players.

Multiple leaders answered his call, sparking the greatest in-season turnaround in NBA history, and while Udoka generally credited health and lineup cohesion — he eventually made sure to mention his wakeup call. Absent from social media, Udoka eventually heard that some people didn’t receive his tough talk toward the team well.

“Like I care.”

The players knew it came with the deal, Udoka emphasizing his relationship-building and directness on the way to succeeding Brad Stevens. Udoka had a plan from Day One centered around making Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown playmakers and building a dominant defense. Getting Marcus Smart more ball time also emerged as an emphasis. Udoka looped Smart in among the franchise’s pillars.

Aside from some fine-tuning, Udoka rarely wavered from his intentions. Starting two big men in Al Horford and Robert Williams. Switching at a rate unmatched across the NBA. He kept his rotations tight and put the onus on the players to figure out how to stop opposing runs without calling a timeout — all while prioritizing the larger picture in perspective. Accountability remained high through some staggeringly bad runs of play. Habits, he said, won’t change overnight for Brown and Tatum. He drilled them anyway and results flowed quickly. Startlingly fast.

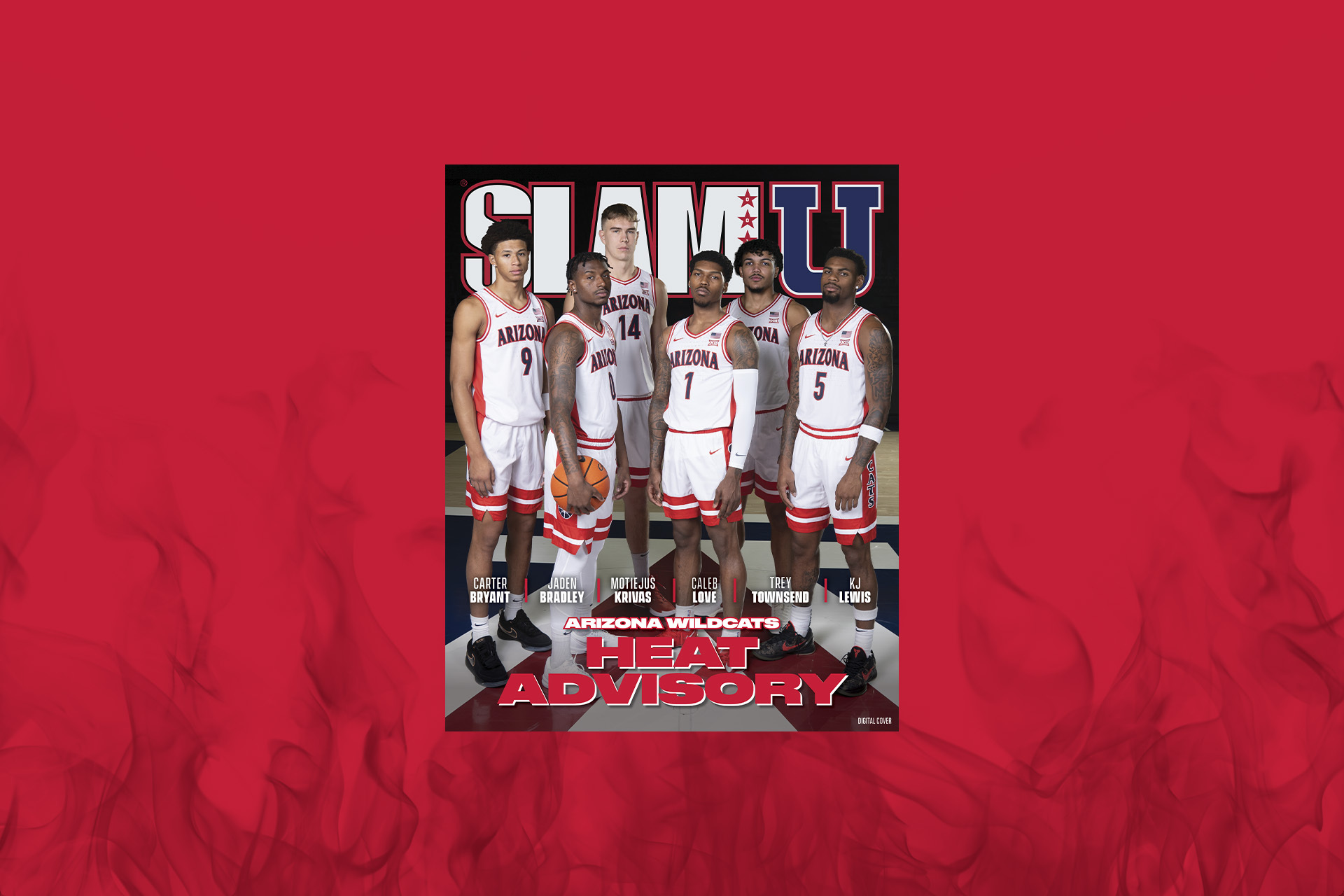

Photo by Maddie Meyer/Getty Images

The entire team was held accountable, including Tatum, and even through one of his worst starts in his young career, Udoka kept simultaneously pressing him and trusting him. Not letting shooting impact defense. Giving the ball up to get it back. Ignoring the officiating. Don’t play in crowds. The balance between utilizing isolation abilities and playing team basketball. Continue to trust teammates even when they weren’t hitting shots. More directly, Udoka told Tatum to find other ways to impact the game as a massive shooting slump overshadowed his start.

Tatum achieved his most well-rounded season as a favorite for First Team All-NBA status — 26.9 PPG, 8.0 RPG, 4.4 APG, 1.0 SPG, 45.3% FG, 6.2 FTA (85.3%). His finishing efficiency at the basket exploded over 65% as he drove more than ever, collapsing defenses and directing Boston’s offense downhill. Boston averaged 1.17 points per possession when he got double-teamed (receiving the 13th-most per game), more than the Nets scored on Kevin Durant’s double-teams (1.16).

“Ime is a really smart guy who has the patience of Job,” Jeff Van Gundy said in December. “No one can be ruffled by the way he coaches … if they can’t get it together under him … then either the group’s not as talented as some think, or they just don’t fit right together.”

That’s where many went as the Celtics spent 111 games between the beginning of last season and the start of this year on an infuriating .500 ride. While Tatum stressed communication in the aftermath of the Knicks collapse and realized long postseason runs weren’t inevitable after all, Brown addressed their relationship, which they long deflected any questions about.

Before a rematch between the Celtics and Knicks in Boston, both affirmed their attentions to figure it out on the same team. The grass isn’t always greener elsewhere, Tatum asserted.

“There were people that was questioning if we were friends, I even seen people say that we didn’t even like each other. I’m like where did they get that from? It was almost as if they made that up. I guess, in a sense, because so many people have talked about it, it’s forced us to talk about it more and I guess it has enforced our relationship in a sense.”

On the court, Udoka stressed the need for the pair to learn how to play together. As they acclimated to more ball time, the number of passes they threw between each other stood staggeringly low compared to other star forward duos like Paul George and Kawhi Leonard. We soon saw things we’d rarely witnessed. Brown and Tatum’s activity, playing in the same area, Tatum even beginning to screen for Brown and slip into the high post to score and pass closer to the basket.

The pair averaged 5-6 passes per night to each other in late November. From that point on, they doubled that total to 12.4 per game. Brown, once lost in the corner during some games, consistently started receiving over 18 shots each night from a variety of positions, including as a lead creator through the winter’s spell of injuries and COVID.

“I think just going through the experience. We got a new team, a new front office, a new coaching staff. Things were different, so we were trying to figure it out,” Brown told CelticsBlog in March. “And while we were figuring it out, it was a lot of x, y and z, but now we made adjustments, we watched film, we had time to take some ‘Ls that we shouldn’t have lost, that hurt, and you learn from those experiences and now we’re kind of just flowing and it’s a little more seamless than it was earlier in the season.”

Brad Stevens leaned into his new role too, taking a back seat from coaching and helping mold a roster around Udoka’s philosophies. Bringing back Al Horford and offloading Kemba Walker, who continued to battle knee ailments into 2022, proved crucial. Dennis Schroder and Enes Kanter didn’t become natural fits for what Udoka wanted to accomplish, and after he tried to make it work with both, Stevens sent them to Houston at the trade deadline and reacquired Daniel Theis, a pivotal move considering the Robert Williams injury. Stevens also paid a steep price for Derrick White, giving up Josh Richardson, a first-round pick and future pick swap. White joined as a natural fit for the team’s ball movement emphasis, and the team’s assist rate that fell to 27th in 2021 leaped into the top-10 in the new year.

Smart then led the way upon his return from COVID and injury in late January. His prominence in directing the offense and transitioning defense into offense became more pronounced. Smart averaged 6.7 assists per game, shooting fewer than 10 attempts per game on 46.1% efficiency, while the Celtics won 23 of the next 26 games he played in.

“I pulled everybody aside right before the tip-off. I told everybody I love them,” Smart said. “I love all you guys. I’m here and proud and really looking for everybody’s success. I’m glad to be a part of everybody’s success … it’s us versus everybody. Nobody really believes in us but us on this team. And that’s how we feel. We hear the noise. We see it. It is what it is. But it’s us versus everybody.”

He remained with the team through the deadline, a credit to Stevens and the front office’s patience. Smart would prove himself in his role over such an extended stretch that he earned his teammate’s respect. Brown recently said Smart did a great job this year. But nobody became a bigger beneficiary of Udoka’s ascension to head coach than Robert Williams.

Stevens told Williams about Udoka after the hiring process. Williams wasn’t familiar with Udoka at that point. He only knew the new coach arrived to challenge them. Williams played over 44 minutes on Opening Night. A clear contrast from how cautiously Stevens managed Williams the season prior. Udoka would later call on the team, generally, to play through pain, something Williams took personally on his way to 61 regular season games.

Stops and transition opportunities turned abundant in early 2022, when Udoka moved Williams III away from the ball. Positioning Smart and Horford to guard the pick-and-roll, while Williams III guarded less dangerous creators like spot-up shooters or defensive specialist wings.

That allowed him to pinch the lane alongside Horford, stopping dribble penetration, or to rotate inside and block shots on the help side. Williams III’s own ability to switch made the scheme nearly impenetrable. In a league oriented around screening into mismatches, the Celtics starters had no single defender opponents could isolate. Trying to attack Williams head-on almost became a welcome distraction.

Across two months, before Williams III tore his meniscus, the Celtics outscored opponents by 16.4 points per 100 possessions overall. Williams III posted a +20.3 net rating during that stretch, helping erase crunch time concerns through sheer dominance Boston hadn’t seen since the start of the 2008-09 regular season.

Tatum, Theis, Horford and a late surge from Brown have continued to steer a No. 1-ranked offense in Williams’ absence. Udoka and the front office have already expressed optimism that Williams can return sooner rather than later, as a difficult first-round matchup looms against either the Cavaliers or Nets. Not only has Boston’s historic turnaround, winning 28 of the team’s 35 games, widened the possibilities for this season. It’s stabilized the group’s core and outlook.

This young roster can continue to grow, gel and contend, while trying to develop contributors around the edges like Aaron Nesmith and Sam Hauser. Payton Pritchard, too, overcame nearly a full season buried on the bench to open his sophomore campaign, breaking out following Schroder’s departure by shooting 50% from three on 80 tries over the team’s final 14 games. Udoka called it, never worrying about Pritchard’s early slump.

Udoka hasn’t taken a moment to reflect on it all. It’s not in his nature. When he does, he’ll realize he produced one of the most impactful seasons by a coach in Celtics history and helped turn the trajectory of the franchise back in the right direction, Coach of the Year or not.

“I haven’t thought about any of that,” he told CelticsBlog last month. “When you’re in it, and you see how coaches think this way all the time, how fragile it is or one thing can kind of offset what you’re doing, so you stay locked in, in the moment, and continue going game-by-game. There are things we can improve, as well as we’ve been doing, so those are the things you look at overall and so our team doesn’t get content, complacent or happy with where we’re at.”